Sometimes when looking at art my thoughts wander outside the white cube. Scenes from grey streets, rough stations and chaotic crowds come to life in my mind. In the case of Alona Rodeh this experience is reversed. As I wander in a city’s streets, whether in our shared homeland city that “never stops” or in any of our new European global residents, Rodeh’s work echoes in my head and in my body. Rodeh is one of those artists whose practice conveys and celebrates the city, the metropolitan space and its materials, sounds and subcultures. Appearing in rhythmic spasms, her work surrounds its viewers (from outside and from within their bodies) and holds a lasting but temporary spectacle which is at once enticing and alienating. This experience, just as in random poetic urban encounters, feels as if you are a stranger to it or as if you just now found a piece of yourself, a scene in which you can belong.

Playfully composed, Rodeh creates sculptures, video works, sound pieces and light installations using what she calls “cultural phenomenons”. Taken from her own experiences, the materials she uses are tangible, non-physical and emotional. Like many other urban agents of our time, emotions for Rodeh are not materials for romantic expression, nor for analytical psychological claims. In her practice she treats emotion as she would any material, which is then translated to frequencies activating the viewer’s body.

As part of a new contemporary art generation of the ‘urban class’, Rodeh is based in two cities –Berlin and Tel Aviv. In the German city, to which she moved in recent years, the artist is currently showing under the ‘meta-title’ Safe and Sound at Vesselroom Project Space and is about to take part in transmediale 2016 with ‘The Chase‘ between January 29 – February 20. Working over the past decade in Tel Aviv, Rodeh established herself as a well-known and original artist in terms of her content and her intuitive approach. Communicating via email she describes her existence between these two cities as “literally jumping in between hot and cold showers”. It’s a description that somehow captures her great ability to translate complex cultural infrastructures into immediate experiences. In a similar way it seems that Rodeh’s roots, coming from a highly complex political environment on the southeastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea, are translated in her work into a sensual presence that surrounds her audience. To put it in her words, “Israel and Tel Aviv are embedded in my work in many ways. My work can say a lot to a non-Israeli audience, but I see how an Israeli audience can recognise more depth in the work. It’s just like that.” Rodeh’s politics, much like the emotions and materials she encounters and gathers, exist for the senses.

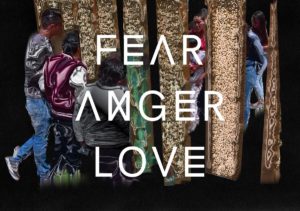

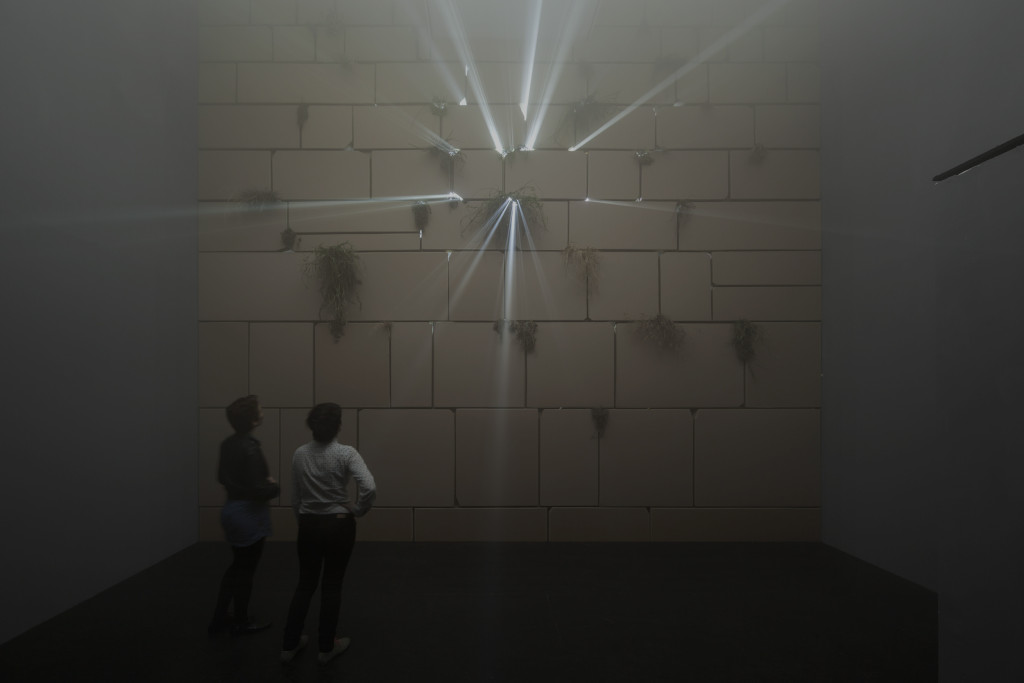

An installation called ‘Above and Beyond’ (2013) replicates Jerusalem’s Western Wall (also nicknamed the Wailing Wall) and transforms the holy site of gathering into an urban disco dance floor. Made out of cardboard, it sits at the end of a darkened gallery space. Approaching it the viewer is faced with direct rays of projected light breaking through its bricks, and a musical piece by musician Yoni Silver composed of hand clapping, whistles and footsteps in a syncopated dramatic beat. In this work Rodeh manages to translate the iconic monument and its age-old religious, political and cultural baggage into an overwhelming and somehow ecstatic secular experience. The political symbol becomes a site of irony. This irony seems to be central to Rodeh’s interest, her artistic gestures are humorous and cool, while holding a certain level of ambiguity which can be encoded only in her viewer’s mind and eyes.

Rodeh defines this piece as one which belongs to an older chapter in her practice: large, complex and correlated monoliths which maintain one channel of energy. After moving to Berlin in September 2013, the artist’s practice took a turn towards being more fragmented. She says she felt that “it might be interesting giving audience dots to connect between” and so started working on pieces that are presented together as one body of work, but do not attempt to function as a complete whole.

The first work presented in this new chapter of Rodeh’s practice was an homage she created to the Israeli Iron Dome (Israel’s recently developed air defence system). The work was entitled ‘Safe and Sound (Iron Dome, Sound)’ (2015) and included a sound installation engulfing the entire museum space, a large scale figurative graphic sculpture and a still photograph. Surrounding the The Crystal Palace & The Temple of Doom group show (held at Petack Tikva Museum of Art and curated by Hila Cohen-Schneiderman) were speakers planted by Rodeh. They emitted disturbing, quick and intense noises that faded in and out in different parts of the space every fifteen minutes. The sounds were composed of sirens, which then turned into dance music tracks, and were created by music artist Harel Schreiber (known as Mule Driver). This homage to Israeli engineered defence technology grew, then, to a paradoxical embrace of urban anxious ecstasy.

In the upcoming transmediale 2016, Rodeh will give a performative talk presenting the more research-based aspect of Safe and Sound. It seems that Alona’s move to Berlin and working “outside her comfort zone” gives her practice a very fruitful ground to grow on, as well as rich new forms and audiences. When I ask her how the project came about she writes in reply:

“By now I call ‘Safe and Sound’ a meta-project, since I don’t see the end of it and for every show/project the emphasis is on specific things, but all in all in the last 2-3 years my work is all around these subjects of visibility of safety in the city. When I say visibility I mean ‘presence’; it can be sonic, behavioural etc… It started with the link between club culture and a sense of security. A club has its own unwritten rules, and when the system works, you can be inside for days and feel very well protected. From there it expanded to the streets and to the different aspects in light, sound, architecture, clothing and more and more.”

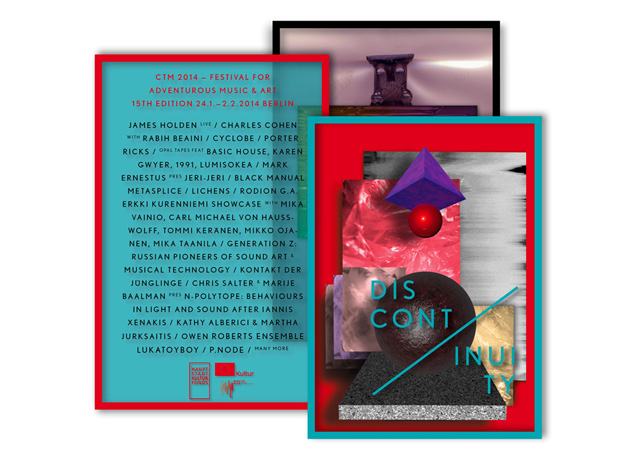

One of Rodeh’s most concise works from this meta-project appeared recently as part of her recent Safe and Sound (Evolutions) exhibition, opened at Berlin’s Grimmuseum in September 2015 and later Tel Aviv’s Rosenfeld Gallery in December. Here the video ‘Rachid’ (2015) shows a man staring beyond the screen. His frozen gaze is disrupted by a flickering red and blue light and the ambience of clubs and sirens implies a scene. The man named Rachid is either facing a police car, or is inside a nightclub. The frozen body animated as a performative object is screened on a light reflecting fabric. The screen agitates the video to transform it into a material or even an object in itself, and the projected and reflective image of Rachid is disrupted by the surrounding environment. The work was presented alongside sculptures, light installations and posters, all inspired by Rodeh’s rich research. Her upcoming talk at transmediale, Fear of Silence, or A Brief History of the Air-Raid Siren will present the history of the siren’s sound and technologies that follow art movements, military uses, international trading connections and more. All will be presented back-to-back with live musical performances by Mule Driver and Siren Diva AKA Haim Vitali. While exchanging emails regarding this text, Rodeh is in the process of finishing her new installed work Safe and Sound: The Chase which is a silent light installation. When I ask her about it she reveals the experimental nature of her practice, saying “we’ll see how that feels. Better bring your sunglasses, I guess.”

Rodeh’s meta-project, which started as an ironic homage to Israeli defence carries her back to a long history of western culture and its manifestations in urban subcultures. It conveys her deeply intuitive and experimental artworks which capture in them some of the anxiety they relate to. Rodeh sees this anxiety as a sort of momentum; within every new work she creates there is always something still unknown, even to her. As her research reveals, the technology and sounds of anxiety which are placed in Israel are very specific, but also connected to European ideas and industries. Anxiety is part of urban culture, and it manifests itself as different spectacles in different cities. As a viewer I feel as if our feelings could be one of the many frequencies she receives and transmits.

Safe and Sound was also manifested in the form of a publication titled Safe and Sound Deluxe, published in collaboration with The Green Box Kunst Editionen. It includes images Rodeh collected as part of her research as well as texts written by Shachar Atwan, Fabrizio Gallanti, and Hillel Schwartz. Just after our correspondence, I’m tempted and order one myself. As no element of Rodeh’s work can remain still, it will arrive with a bag made out of light reflective fabric. It is as if the artist is trying to spread the presence of safety agents into new urban territories. As I get on the bus one day I encounter two policemen wearing bright yellow reflective light vests. I feel a bit anxious and stressed. I don’t know why, but instead of feeling safe I start to panic. Then I remember the character ‘Rachid’, and I imagine how this would feel if I was wearing Alona Rodeh’s bag. I would probably walk past them feeling safer and my mind would break out onto the dance floor. **